Every couple of weeks we see a new article come up that tries to answer the good old question: should designers learn to code? Our industry is finally reaching a point where we are able to step back and reframe that question altogether.

There are two fundamental arguments used by those who defend the fact that designers who learn to code become more valuable than others:

First, by creating prototypes that are as close as possible to the ultimate intent of the desired experience, it becomes more likely that it will be executed by others appropriately — if not by the designer itself.

Second, the more a designer can speak the language of their developer peers, the better they can collaborate to get to a stronger final product.

Of course designers should know how to code. This is about being a good artisan and knowing the materials you’re dealing with.

Of course designers shouldn’t spend all day creating code. This is as inefficient as asking an architect to build a wall herself.

However, it turns out we were asking the wrong question all along.

As Dave Malouf points out in “To code or not to code? OMG! This is totally the wrong question”, while both of these arguments are truisms and irrefutable in their framing, they also continue to ignore all of the data that suggests that there are consequences to these truths — creating a unique paradox of logic.

Relying on designers being able to code can be a symptom of systemic oppression in the workplace. “As a designer, I will go out of my way to speak the language of those who hold power, to assimilate, so they will trust me. At the heart of this [contradiction] is the foundation of anthropology and the notion of balancing the outsider and insider perspectives to bring understanding through comparison. I am only as valuable as a designer as I am able to maintain that balance between the outsider and insider perspectives and to hold the mindset of student/apprentice.” — states Malouf.

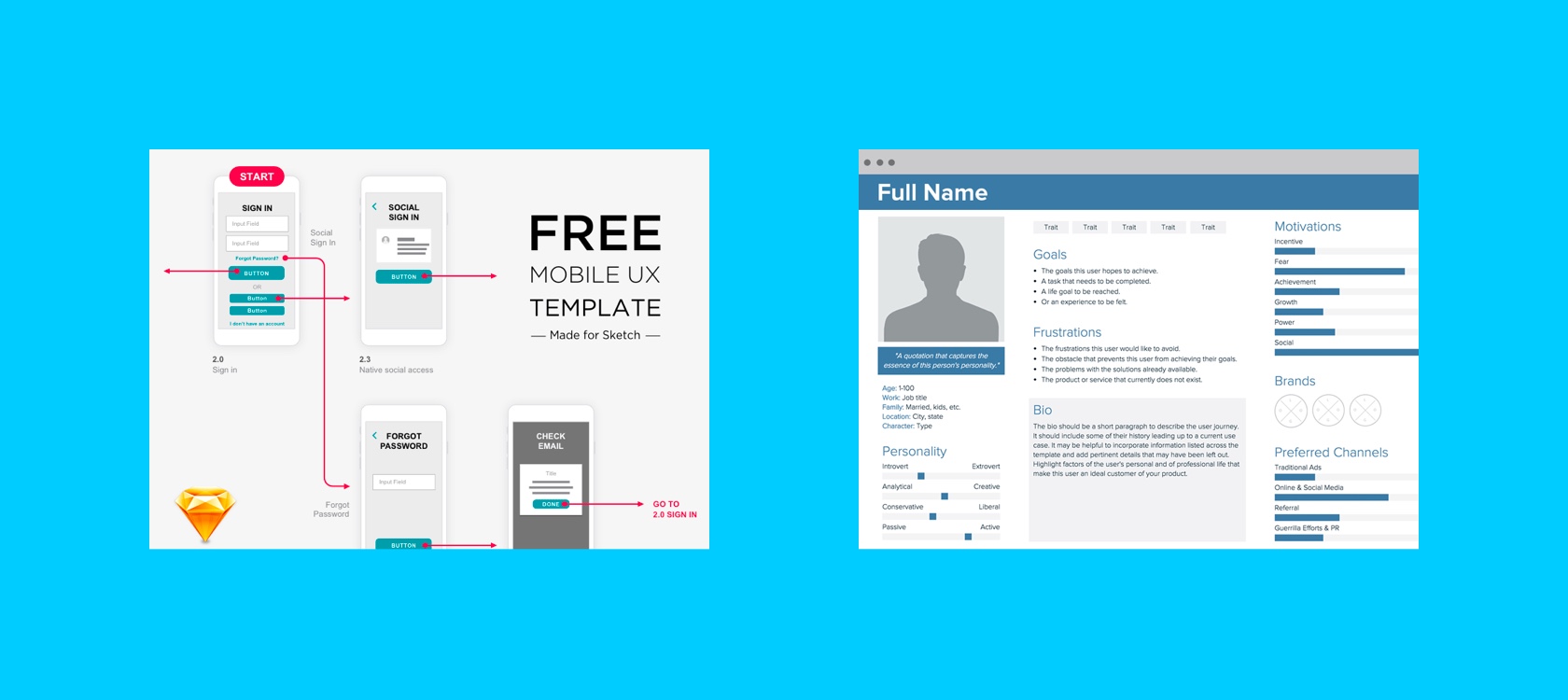

In parallel to this never-ending discussion, we have been observing an ongoing evolution of the design tools we use everyday that enable designers to go back to focusing on what they are really good at: designing (big surprise).

In 2018 we have seen a few transformations that corroborate that trend:

Principle has become one of the most popular UI prototyping tools, requiring almost zero knowledge of coding and native coding languages;

Companies like Airbnb have developed internal workflows that allow designers to sketch a UI on paper, and spit out code in a matter of seconds, bridging the gap between designers and engineers working on design systems at scale;

New tools like Framer X and Modulz have evolved to be able to automatically translate UI patterns into React components, which means in most cases developers can build upon designs instead of replicating them in production;

Tools like Hadron App have started to unify Design and Dev workflows into a single UI that has two distinct “views”.